An essential part of Tahiti’s history.

The islands of French Polynesia have long been a popular destination for queer travellers, but the Polynesian culture also has a fascinating and ancient history with Māhū – a distinct third gender. Like the two-spirited people of Indigenous North America, or Thai kathoey, the Māhū were born men…but embrace their feminine energy.

They were first documented in the 16th century.

The earliest known reference to the Māhū people was in 1789. William Bligh, Captain of the Bounty, wrote in his logbook about “people very common in Otaheitie called Mahoo…who, although I was certain was a man, had great marks of effeminacy about him.” Notably, they weren’t just tolerated but embraced as caretakers of children and the elderly. Even back then.

Being Māhū wasn’t a ‘medical condition’.

Unlike modern Western society, which dives into the psychiatry of the individual and gender identity, being Māhū is considered a culture-bound transsexuality with a distinct – and respected – history. An Māhū was definitely different, but there was nothing unusual about this third gender. For example, if a young boy exhibited feminine energy, they would simply be raised alongside the girls. Rather than hunting or going to war, they would sing and dance with women…, and it was no big deal. They were even respected and trusted enough to become servants of the noble class once they grew older.

They survived Colonialism.

There was nothing great about Colonialism, especially when it came to encounters with anyone ‘different’. But while the Māhū may not have been loudly embraced by the newcomers, they were not extinguished. Colonists realized they were an important element of domestic help and sometimes downright essential…whether they wanted to admit it or not.

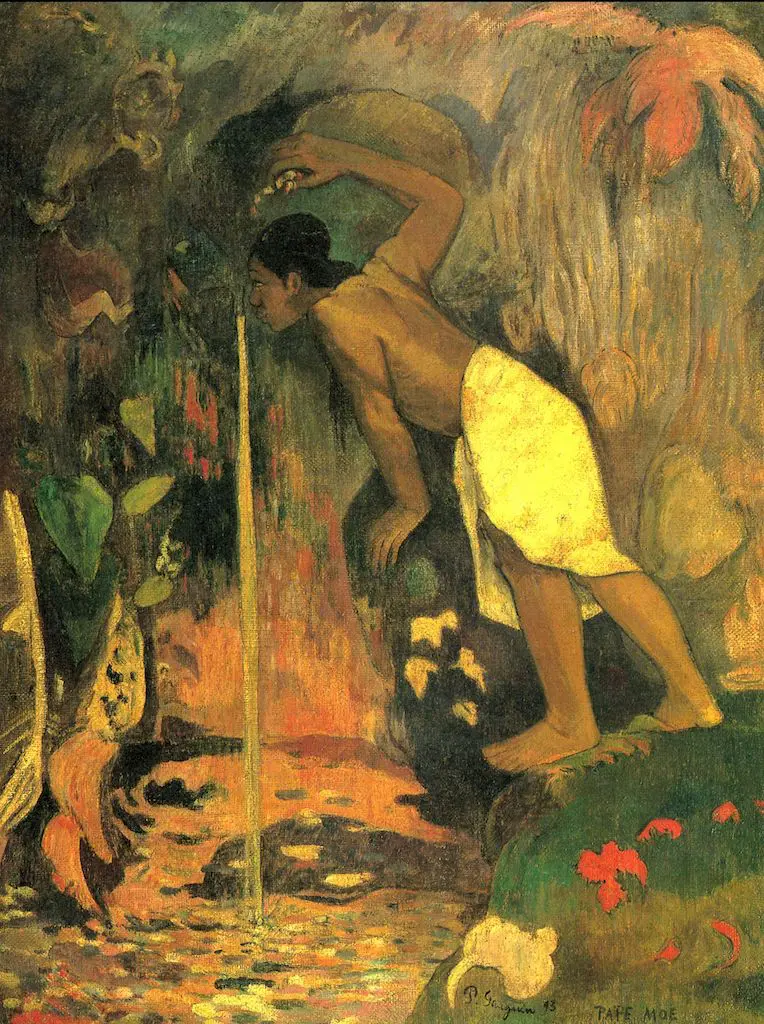

French painter Gaugin was mistaken for a Māhū.

When the French Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gaugin first came to Tahiti, he was thought to be a Māhū by the indigenous people. His hair went down to his shoulders, and he wore a flouncy cockade with red fur. His clothes were flamboyant, almost scandalous, and he was fascinated by the exotic sensuality of the islands’ people. On the other hand, he also married a thirteen-year-old Tahitian girl…but that warrants a completely different discussion. While here, much of the art he created did feature people of ambiguous gender.

Māhū performed the roles of goddesses in hula dances that took place in temples which were off-limits to women. Māhū were also valued as the keepers of cultural traditions, such as the passing down of genealogies. Traditionally parents would ask māhū to name their children.

-master hula teacher Kaua’i Iki

They were the original Hawaiian settlers.

Long before Captain Cook “discovered” Hawaii, the islands were populated by Polynesians. It’s believed the first settlers arrived in the 11th century. What we love is the folk tale of four magical Māhū that brought their healing arts from Tahiti. The leader was named Kapaemahu. Along with fellow healers Kahaloa, Kapuni, and Kinohi, they infused boulders with their power before returning to court in Tahiti. Those stones were rediscovered and moved to a permanent home on Waikiki Beach in 1997. You can watch a short film about the tale below.

Unfortunately, while trusted to look after children and elders in their family, Hawaiian Māhū wouldn’t necessarily be trusted in positions of power. Some felt they were always available for sexual conquest by men. By the nineteenth century, biblical (anti-sodomy) law was imposed on the islands. The Māhū were shunned. By the mid-1960s, Honolulu City Council even forced trans women to wear badges asserting their ‘male’ identity.

Then there is Rae-Rae.

Emerging in the 1960s, rae-rae were Mahu that didn’t just embrace their feminine side but actually became trans women. Unfortunately, this also led to more complication and confusion. While Māhū were considered soft and sweet, many see rae-rae as vulgar. They had gender reassignment and cosmetic surgery. They often resorted to sex work and were then judged for promiscuity (rather than becoming an integral and innocent part of the home and family). Some use the term interchangeably but to the chagrin of older Māhū (who may even embrace chastity).

Māhū today.

As societal norms evolve, the term now encompasses a broader scope of gender and sexual orientation. They participate in beauty pageants, but Māhū can also be found working in hospitality, and in the arts, and some have become well-known local personalities. You may even see them at church – wearing their Sunday best – without anyone batting an eye. In this CNN article, you can even see modern Māhū captured beautifully in a series of portraits.

If you’d like to celebrate this important part of Polynesian culture, join us on our Tahiti & Bora Bora Gay Cruise.